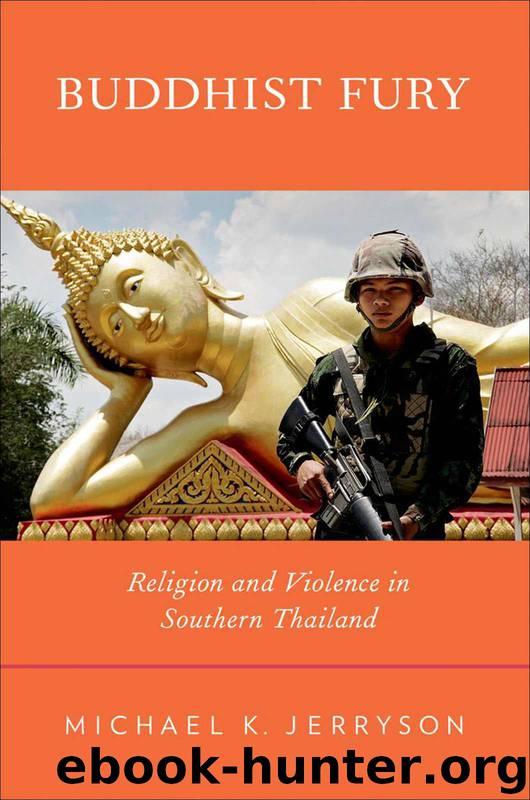

Buddhist Fury: Religion and Violence in Southern Thailand by Jerryson Michael K

Author:Jerryson, Michael K. [Jerryson, Michael K.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Oxford University Press, USA

Published: 2011-06-29T00:00:00+00:00

Race/Ethnicity in Thai Studies

An examination of race and ethnicity illuminates systemic and hegemonic processes that cut deep into the economic, political, and social domains of the country. Race and ethnicity also refer to interrelated, but distinctive and commonly used identity markers of peoples in the three border provinces. This, above all else, necessitates time spent on the subject, but the topic also has a secondary and equally important purpose. The focus on race and ethnicity reveals the biases implicit in academic investigations into Thai economic, political, and social processes. For these reasons, we will first define race and ethnicity and then look at how significant cultural factors influenced the way that scholars studied peoples in Thailand.

Race is a complex and commonly misused term. To avoid many of its pitfalls, I will employ the terms “racial project,” and “racial formation” in my discussion of race in accordance with the categories established by sociologists Michael Omi and Howard Winant. Omi and Winant argue that race is “… an unstable and ‘decentered’ complex of social meanings constantly being transformed by political struggle.”6 Though unstable, the race identification is continually affirmed through a public sphere saturated with racial projects—physical and oral references that essentialize peoples, such as significations found in Mongkon’s report. In a likewise fashion, racial formation is a process “by which social, economic, and political forces determine the content and importance of racial categories, and by which they are in turn shaped by racial meanings [emphasis added].”7 While Omi and Winant’s work is specific to identity formation in the United States, as a theoretical rubric their work offers an analytic to assess the process of grouping and discriminating peoples in societies such as Thailand, which share common trends of applying skin color, class, and immigration politics toward national selfhood.

In contrast to race, I use ethnicity as an endonymic nomenclature, which derives from the reflection of self-ascribed groups of people, rather than a name given to peoples. Tambiah expresses the collective, yet internally derived identification quite clearly in his orientation of ethno-nationalist violence in Leveling Crowds: “Ethnic identity is above all a collective identity: we are self-proclaimed Sinhalese, Malays, Ibos, Thais, and so on.”8 In this regard, ethnicity is an internally derived social marker, which falls prey to just as many primordialist claims as those that are externally derived. The difference between race and ethnicity lies in who does the naming.

Both ethnicity and race have been used in academic analyses of Thailand. Thomas Hylland Eriksen reviews the connections between ethnicity and Thai nationalism and draws upon the seminal work of Michael Moerman.9 For Eriksen, cultural difference between two groups “is not the decisive feature of ethnicity.” Instead,

the groups must have a minimum of contact with each other, and they must entertain ideas of each other as being culturally different from themselves. If these conditions are not fulfilled, there is no ethnicity, for ethnicity is essentially an aspect of a relationship, not a property of a group [emphasis added].10

Thus, “Tai” and “Malay” refer to

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Way of Zen by Alan W. Watts(6587)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5400)

The Art of Happiness by The Dalai Lama(4118)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3965)

Why Buddhism is True by Robert Wright(3439)

Spark Joy by Marie Kondo(3292)

Shift into Freedom by Loch Kelly(3190)

Happiness by Matthieu Ricard(3037)

A Monk's Guide to a Clean House and Mind by Shoukei Matsumoto(2901)

The Lost Art of Good Conversation by Sakyong Mipham(2638)

The Meaning of the Library by unknow(2557)

The Unfettered Mind: Writings from a Zen Master to a Master Swordsman by Takuan Soho(2291)

The Third Eye by T. Lobsang Rampa(2255)

Anthology by T J(2202)

Red Shambhala by Andrei Znamenski(2180)

The Diamond Cutter by Geshe Michael Roach(2056)

Thoughts Without A Thinker: Psychotherapy from a Buddhist Perspective by Epstein Mark(2007)

Twilight of Idols and Anti-Christ by Friedrich Nietzsche(1886)

Advice Not Given by Mark Epstein(1873)